August 9, 1942

Aug. 9, 1942

The United States and her Allies are on their heels in the Pacific. Japan looks invincible. From December until June, Japanese forces had over run Wake, Guam, the Philippines, Java, Malaysia, the Caroline Islands, the Marshall Islands,

Everything had been going Japan's way up until they were turned back at the Battle of the Coral Sea and were defeated soundly at Midway on Jun 4th.

The United States and her allies Great Britain and Australia decided on a time and place to launch their first offensive. The time: August, 1942. The place was an island that no one had ever heard of in the Solomon Islands called Guadalcanal.

Nimitz staff called it Operation Watchtower. The men of the 1st Marine Division called it Operation Shoestring: everything was a mixture of WWI leftovers, troops and specialists gathered from as far away as British Isle and a collection of aircraft that were overdue for retirement for the most part. The navy put together the best cruiser/destroyer force that it could and gathered up as many transports as they could find.

On August 7th, the Marines landed on Guadalcanal. They surprised a small Japanese advanced force of engineers that had already landed on the island and were preparing an airfield. The land battle for the island was joined. The Marines were equipped with old WWI era Enfield rifles and were under-strength in machine guns.

Guadalcanal, like most of the Solomon Islands is a rugged and dominated by thick jungle, miserable swamps and malaria carrying mosquitoes. Over the years it had been home to an aborted sugar plantation, a way station, a mission, a trading post and finally an Australian cattle ranch.

When the Marines landed they found themselves in a fast moving fire fight with an enemy that was not prepared or dug in. Both sides found themselves short on supplies. They raided the barbed wire fences of the cattle plantation for materials to build their perimeter with. In a series of actions, the Marines and the Japanese fought a number of small unit battles- and one that both sides had to call off because of a cattle stampede.

Over the next day the Marines continued landing troops, supplies, artillery and combat engineers. They established a firm bridgehead and formed a firm perimeter around the unfinished airfield.

The Japanese were not sitting on their hands. The same day of the invasion, area commander Admiral Mikawa dispatched two fast transports with crack Naval Special Landing Force but recalled them when reconnaissance determined the scale of the allied incursion. Frustrated, he had to wait a day to fuel his ships and gather his forces to attempt to repel the invasion.

At Guadalcanal the US Navy continued with support activities and continued to unload transports onto the beachhead. At night on August 8th, Admiral Turner's Task Force 62 and Australian Rear-Admiral Victor A.C. Crutchley's combined support/escort force broke into three groups: a Northern force to cover the pass north of Savo Island, A Southern force to cover the pass south of Savo island and a pair of destroyers to cover to Weatern approaches.

Northern Force: cruisers USS Vincennes, USS Astoria and USS Quincy, and destroyers USS Helm and USS Wilson

Southern Force: cruisers HMAS Australia and HMAS Canberra, cruiser USS Chicago, and destroyers USS Patterson and USS Bagley

Western Screen: destroyers USS Talbot and Blue

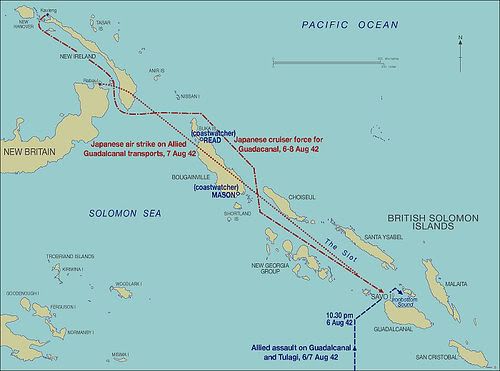

Mikawa set sail from Rabaul in the heavy cruiser Chokai, light cruisers Tenryu and Yubari and the destroyer Yunagi. They rendezvoused with Admiral Goto's Cruiser Division 6 composed of heavy cruisers Aboa, Kinugasa, Kako and Furutaka. Their goal: to take on the US Navy in a night action.

Mikawa's Approach.

The US Navy was just deploying radar on their ships but the first generation sets were unreliable and there were few technicians and no experienced operators.

Mikawa's run down the body of water that would come to be known as "the Slot" was undetected- or at least unreported. Australian seaplanes spotted the ships as did the US sub S-38 but this information did not make it to Admiral Turner's staff.

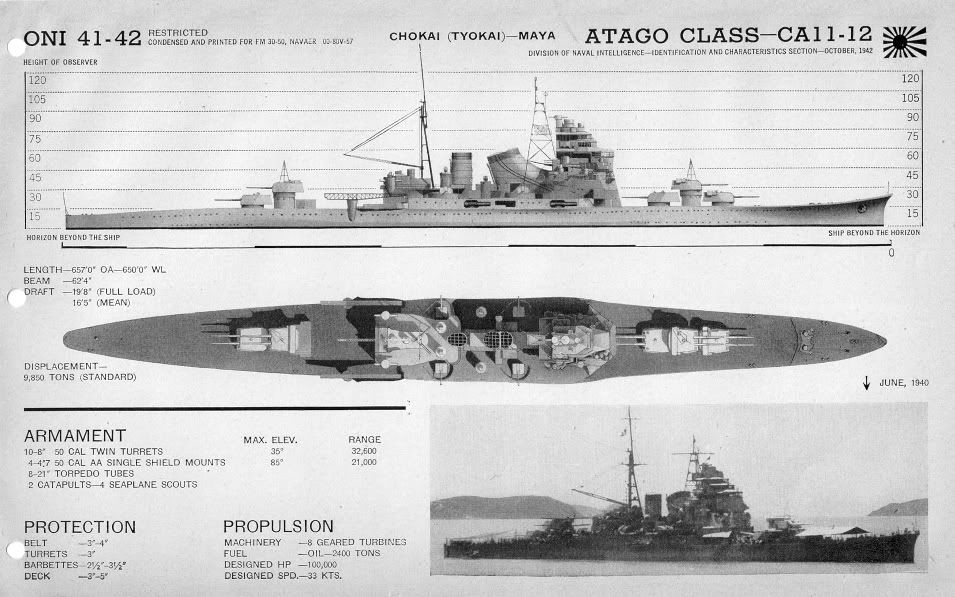

US Navy identification page for Mikawa's flagship the Chokai.

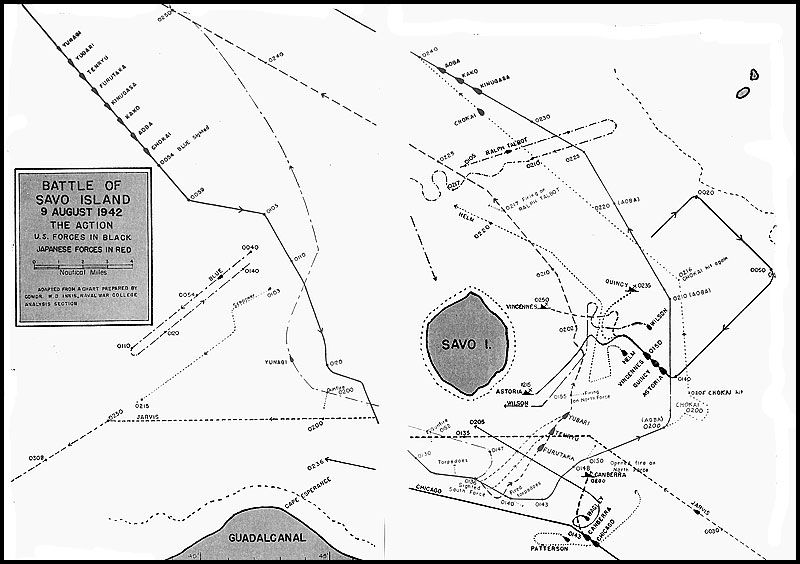

The Japanese arrived just before midnight and slipped past the destroyer Blue and savaged the Southern Force, turned North and savaged the Northern force and left the area the way that they arrived.

The Battle of Savo Island

Japanese long-lance torpedoes destroyed the USS Vincennes, USS Astoria and USS Quincy and damaged the HMAS Canberra so severely, she had to be scuttled. The Chicago was severely damaged but she would fight again.

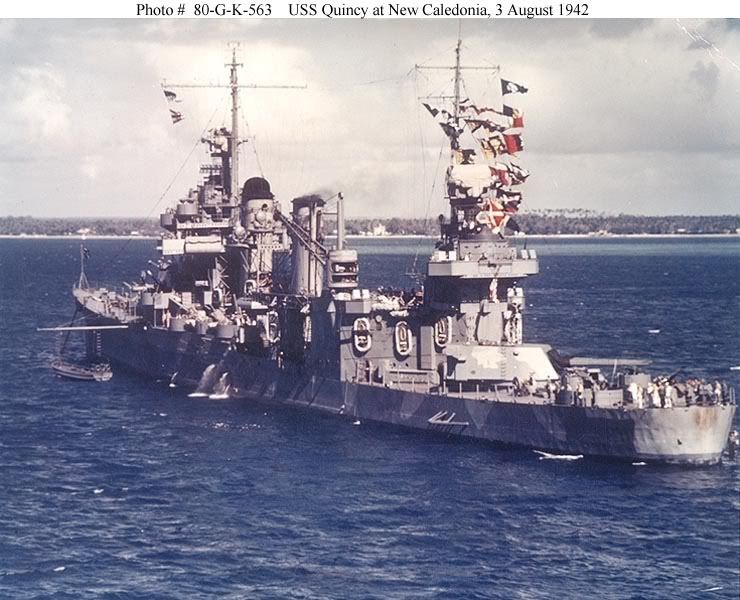

The USS Quincy (CA-39) days before the battle.

The submarine S-44 exacted a bit of payback sinking the cruiser Kako as she retired to her home base at Kavieng.

It was the worst defeat in US Navy history in a stand up fight. The Navy lost 1,207 men: more men than than the Marines lost during the entire 6 month campaign.

This battle was the beginning of a six month long air, land and sea campaign that turned out to be a meat grinder for both sides. The body of water around Savo Island was nicknamed "Ironbottom sound" and would be the scene of several pitched naval battles. The Guadalcanal campaign became a battle of attrition and by the time Japan gave up on recapturing the island in early '43, much of her naval power, best commanders and army units had been expended.

In 1943 the US Navy court of inquiry was held called the Hepburn Investigation. Only one officer was singled out for offical censure- the captain of one of the cruisers. He killed himself when he learned of the boards results.

The board stopped short of calling for action against Admirals Fletcher, Turner, McCain, and Crutchley who went on to perform brilliantly later in the war.

The board of inquiry determined that US ships required more training in night fighting and training and standardization of radar equipment.

Both radar picket ships (radar range about 10 miles) were at the extreme ends of their patrols sailing away from the Japanese fleet. San Juan had modern search radar, but was at the other end of the Sound.

After the war, Admiral Turner wrote:

The (U.S.) Navy was still obsessed with a strong feeling of technical and mental superiority over the enemy. In spite of ample evidence as to enemy capabilities, most of our officers and men despised the enemy and felt themselves sure victors in all encounters under any circumstances. The net result of all this was a fatal lethargy of mind which induced a confidence without readiness, and a routine acceptance of outworn peacetime standards of conduct. I believe that this psychological factor, as a cause of our defeat, was even more important than the element of surprise.

__________________________________________________________

The Battle of Savo Island, Wikipedia entry.

Guadalcanal Frank, Richard B., Penguin, 1993. 0140165614

The Two Ocean War Morrison, Samuel Eliot US Naval Institute, 1963. 1591145244

History of US Navyal Operations in World War II: Volume V. The Struggle for Guadalcanal Morrison, Samuel Eliot US Naval Institute, 1949. 0785813063

4 Comments

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now